Discover more from @amuse

Newspapers, if they are to serve their proper function, ought to refrain from the crude practice of endorsing political candidates. The endorsement is a relic of the age when newspapers were more akin to partisan broadsheets than the ostensibly neutral purveyors of information they claim to be today. It is curious, then, to observe some in the journalistic establishment, such as The Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post, step away from this antiquated indulgence. One hopes this signals a recognition that their role is to inform, not to campaign. Perhaps, at long last, these institutions will embrace true diversity—not the cosmetic kind that the modern left so ardently trumpets, but the diversity that comes from the vigorous exchange of ideas from all points on the ideological spectrum.

Endorsements are inherently problematic for institutions that claim to stand above the political fray. Historically, newspapers had little qualm about their partisanship, acting openly as propaganda vehicles for one party or another. Yet, as journalism evolved, a pretense of neutrality began to emerge, and newspapers claimed the mantle of "objectivity." The endorsement, however, drags these institutions back into a partisan muck. By openly supporting one candidate, a newspaper reveals its bias—negating any claim it has to being a neutral observer of the political landscape.

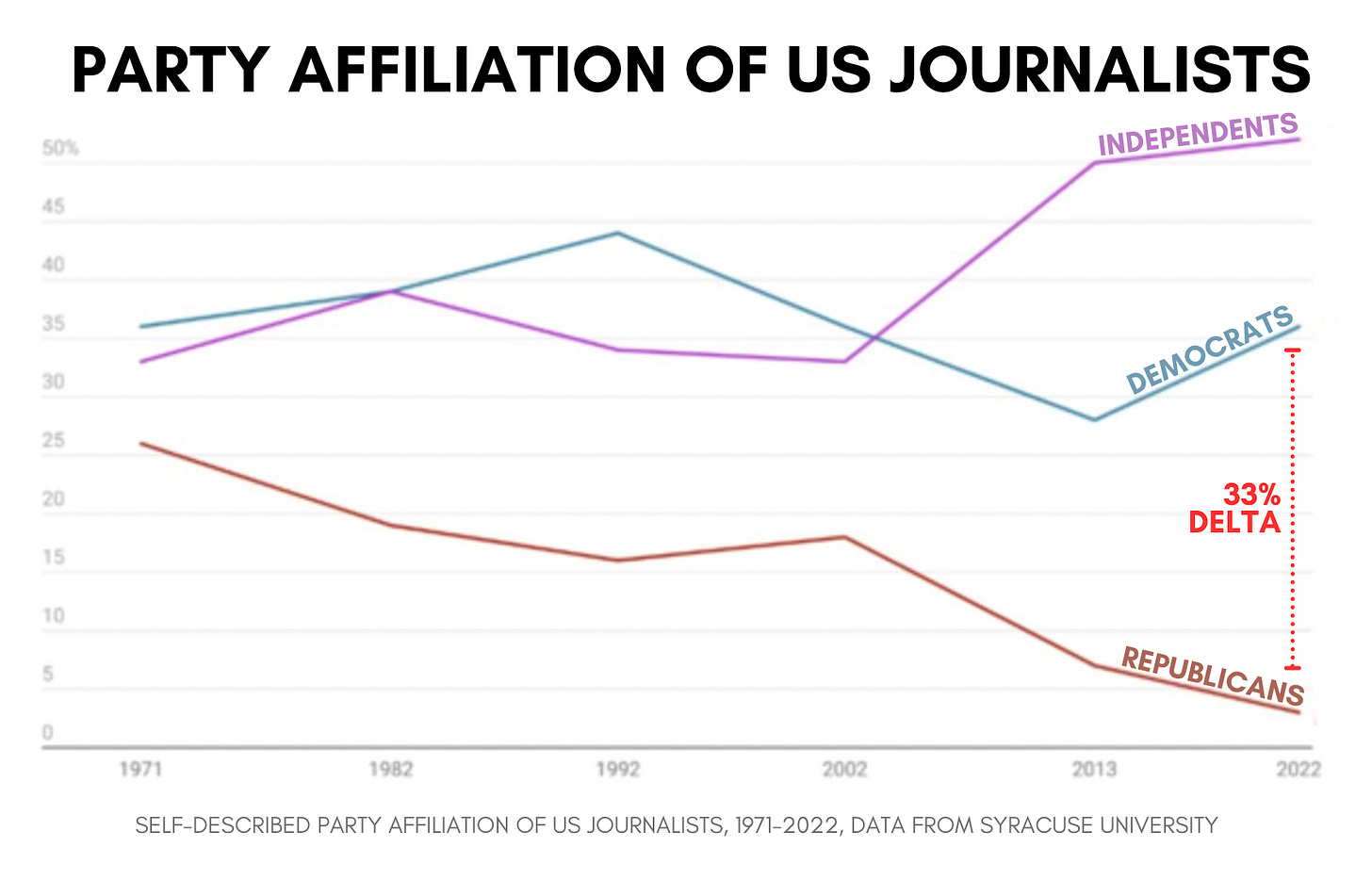

One of the most egregious problems in today’s media landscape is the utter lack of balance in newsrooms. Newspapers, particularly large ones like The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times, have become left-wing echo chambers. The boards that choose to endorse political candidates are dominated by journalists and editors who operate within a narrow ideological range. The Los Angeles Times, for instance, was poised to endorse Kamala Harris in the 2024 election, a decision blocked by its owner, Patrick Soon-Shiong. Similarly, The Washington Post appeared to be leaning toward Harris as well, though owner Jeff Bezos ultimately decided against endorsing any candidate this cycle.

What has followed in the wake of these decisions are resignations from the far-left activist journalists who dominated these institutions. Kevin Merida, the executive editor of The Los Angeles Times, resigned after clashing with Soon-Shiong over the direction of the paper’s endorsements and editorial decisions. At The Washington Post, editor-at-large Robert Kagan stepped down, dissatisfied with the decision to hold back the endorsement. While these departures may be seen by some as negative, perhaps they will finally make room for real balance and diversity in the newsrooms—something sorely lacking today.

These resignations create an opportunity to invite conservative voices and perspectives into spaces that have long excluded them. A newspaper that truly serves its readership will seek to engage with, rather than dismiss, viewpoints from both sides of the political spectrum. The sad truth, as it stands, is that the vast majority of editorial boards are monolithic in their worldview, staffed with individuals who come from the same progressive echo chamber. They hire from the same institutions, run in the same social circles, and—unsurprisingly—endorse the same left-wing candidates. What would be truly groundbreaking is for these institutions to recognize that true diversity means ideological diversity.

Diversity, if it is to mean anything, must include voices from both the right and the left. Today’s newspapers hire journalists overwhelmingly from a left-leaning pool, often ignoring or outright rejecting conservative viewpoints. The American political spectrum is broad and varied; our media ought to reflect that. For too long, conservative ideas have been ridiculed or ignored in major newsrooms, depriving readers of a full and nuanced understanding of the world. The more voices we have at the table, the more robust our discourse will be. Imagine the potential of a newsroom where both left- and right-wing journalists debate the merits of policy, offering readers a full spectrum of opinions.

A 2011 study by Chiang and Knight on media influence shows that endorsements are not just opinion—they shape voter behavior. Newspapers may pretend to simply provide information, but the reality is that endorsements have a significant impact, increasing a candidate's vote share by up to five percentage points. But here’s the catch: it’s not merely an objective evaluation of candidate merits driving these endorsements. According to a study by Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science, newspaper endorsements are deeply influenced by the biases of their editorial boards and owners. This is not journalism—it’s campaigning.

It’s also worth noting that while some might argue that endorsements simply formalize what everyone already knows, this only underscores the problem. Readers of The New York Times expect the paper to endorse a Democrat, just as readers of The Wall Street Journal expect a Republican endorsement. The problem is, these endorsements reinforce the partisanship in our political system, with each side retreating to its respective media bubble. This does nothing to challenge or inform the public—it merely serves to confirm their biases.

Newspapers should take this opportunity to reclaim their original role as purveyors of information. Their job is not to tell voters how to think, but to provide them with the tools to make their own informed decisions. By endorsing a candidate, a newspaper sends the signal that it has already decided who is best, subtly guiding its readership toward a particular outcome. This is antithetical to the principles of good journalism. The goal of the press should be to present the facts as they are, not to push an agenda.

The decisions by The Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post to refrain from endorsing a candidate in 2024 are a step in the right direction. These institutions, once so mired in partisanship, have a chance to lead by example. Let the resignations of activist journalists be the first step in making room for conservative voices, for real balance, for true diversity of thought. It is high time that the media stop trying to be players in the political game and return to their proper role as referees.

In the end, newspapers that abandon political endorsements are embracing a more honest and transparent form of journalism. By doing so, they can better serve their readers—not as political activists, but as the gatekeepers of truth in an increasingly fractured world.